No, Human Races Do Not Exist: Why the Science is Clear and the Language is Lethal

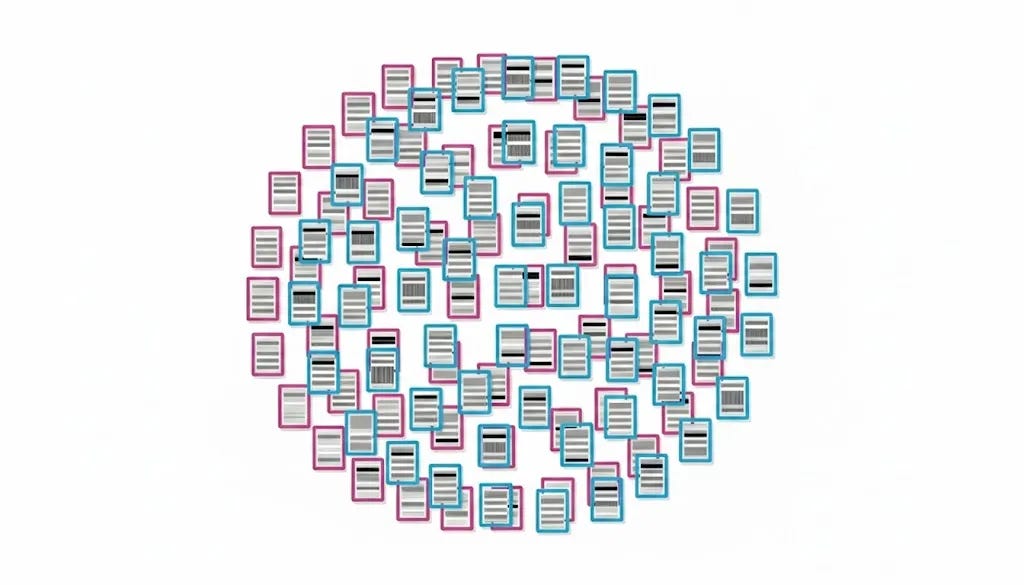

And The Genealogy of a Myth

Most people still believe that distinct human races are biologically real. Even intellectuals on platforms like Substack routinely refer to supposedly separate biological races.

They’re wrong. Research has demonstrated repeatedly that discrete biological human races do not exist. Human genetic variation does not cluster into natural racial categories. The classifications we use are based on arbitrary traits like skin colour, not meaningful genetic boundaries.

I argue that the real danger lies in the language games we create through using these terms. When we categorize humans into “races,” our minds begin to see boundaries where none exist. We start perceiving discrete groups rather than continuous variation, attributing group characteristics to individuals.

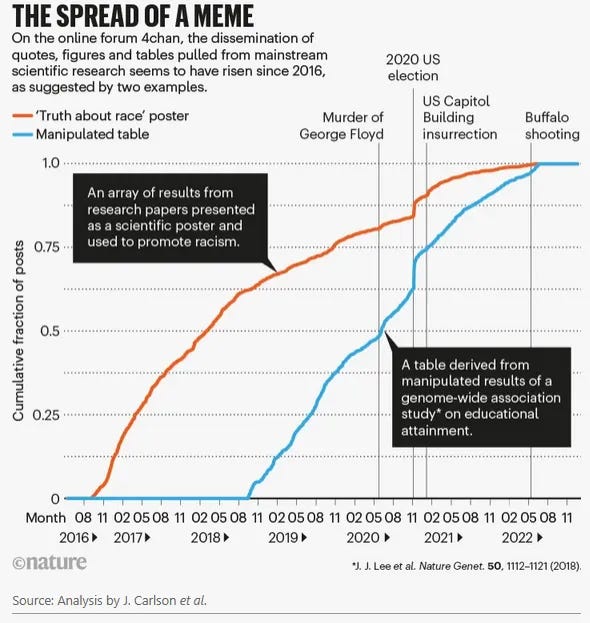

This matters because racist ideologies depend on this linguistic illusion. The concept of biological race emerged historically to justify colonialism and slavery, and it continues to provide apparent scientific legitimacy for discrimination today. For example, the 2022 Buffalo shooter cited a scientific study, he misunderstood, in his screed, to justify murdering ten Black people.

Hence, today, my aim is to clarify this once and for all: Humans do not come in biologically discrete races. Racial categories are social constructions rooted in history, not reflections of genetic reality. And the language we choose actively shapes whether we perpetuate or dismantle that construction.

The Genealogy of a Myth

From Polis to Outsider: The Ancient Roots of Exclusion

To dismantle the idea that biological human races exist, we must examine the historical foundations of the theory. Why did this classification emerge? The roots trace back to antiquity.

In his ethical framework, Aristotle distinguished between members of the Greek polis, who were considered full citizens, and various “barbaric” peoples. He claimed that essential cultural and character differences existed between the Greek polis and other groups.

Thus, Aristotle’s ethics were exclusionary. His foundational idea that eudaimonia is achieved through the exercise of reason presupposed that the capacity for reason was characteristic of a specific group rather than all humans. Here we see the early notion that different kinds of people possess different “natures” and that only some are bound by the natural law of reason. Aristotle therefore based an ethical system on the presumed nature of a single group. Moreover, women were entirely excluded from this framework (Geulen, 2007, pp. 19–23). The Romans adopted this distinction between “barbarians” and the citizens of an orderly state.

With the rise of Christianity, however, a new classification system emerged. This system differentiated humans based on religion rather than origin. The categories became Christians, Jews, heretics, Muslims and so forth. This framework remained dominant well into the modern era (Geulen, 2007, pp. 24–32).

Blood Over Belief: The Inquisition and the Invention of Lineage

However, this framework became problematic during the Reconquista in the 1490s. Under the Spanish Inquisition, Christians forced thousands of Jews to convert to Christianity. Because many converts continued to practice their original religion in secret, religious identity no longer served as a reliable classification. A new distinction was needed. This gave rise to the idea of limpieza de sangre, or “purity of blood” (Geulen, 2007, pp. 32–36). This marked the return of a classification system based on presumed lineage and origin rather than just belief. The Reconquista thus represents the re-emergence of an idea that went beyond religion to introduce a proto-racial concept rooted in blood and ancestry (Geulen, 2007, p. 37).

The Enlightenment’s Dark Shadow

The modern conception of race crystallized with colonialism, the transatlantic slave trade, and the conquest of the Americas. Early theories were shaped largely by reports from missionaries. Unsurprisingly, these accounts were strongly racialized (Geulen, 2007, p. 41). A particularly influential notion was the idea of the “Noble Savage” along with religious interpretations grounded in the biblical Genesis. In these accounts, Europeans attempted to fit Indigenous peoples into a biblical framework by equating them with the “lost tribes of Israel” (Mosse, 2006, pp. 34).

During the Enlightenment, the desire to classify humans merged with the biological notion of the scala naturae. This suggested a hierarchical ladder of beings where value could be inferred from biological characteristics. Travel literature of the eighteenth century began depicting “wild peoples” as less worthy, closer to animals, and of lower moral and intellectual value. For the first time, a hierarchy of supposed human worth was established (Mosse, 2006, pp. 28—31).

Carl von Linné, the creator of the biological classification system in the Systema Naturae of 1735, applied this hierarchical thinking to humans. He classified Europeans, Americans, Asians, and Africans according to skin color while attributing temperament to each group (von Linné, 1758). For example, he described the “red” Americanus as choleric, the “white” European as sanguine and muscular, the “yellow” Asiaticus as melancholic, and the “black” African as phlegmatic and sluggish. These categories mapped pathological psychological traits onto entire human groups (Kattman, 2019).

Immanuel Kant and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach adopted similar ideas. Kant treated white Europeans as the primary bearers of ethical agency. He assumed that they alone had a natural disposition toward rationality (Geulen, 2007, p. 57-60; Kleingeld, 2007). Similar to Aristotle, he claimed other “races” lacked this inherent rational tendency. Kant also believed that different races were capable of different levels of education and that rationality decreased as one moved into southern climates. Blumenbach later emphasized the term “Caucasian” and was the first to explicitly speak of a “Jewish race” (Geiss, 1988) .

The Nineteenth Century: Institutionalizing Racism in Science

After Darwin’s evolutionary theory in the nineteenth century, the biologization of ethnological theories surged. Even though these theories, contrary to Darwins, were purely pseudoscientific. As colonial expansion intensified again, race theory became institutionalized within the sciences (Geulen, 2007, p. 69). Through phrenology and physiognomy, mental and moral characteristics were tied to racial identity and skull shape. A famous example is Edward Long’s History of Jamaica (1774), which asserted a fundamental difference between whites and Blacks (Long, 1774; Mosse, 2006, p. 43).

Here again, the idea of “pure blood” became central. Arthur de Gobineau, in his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1852), wrote about the supposedly harmful effects of cultural mixing (de Gobineau, 1852). He argued it was necessary to preserve a superior European white race because other races were thought to exert a negative influence. Gobineau was also one of the first to use the term “Aryan” in a linguistic and cultural sense. He imagined the Aryan Herrenrasse (master race) as the highest bearer of civilization (Geulen, 2007, p. 74; Mosse, 2006, pp. 67–68).

With the misuse of Darwins theories, the assumption of different evolutionary lineages was absorbed into eugenic thinking. This culminated in Social Darwinism in the twentieth century. Humans were divided into three “great races” known as Europid, Mongoloid, and Negroid. Once again, hierarchies were drawn between “high-quality” and “low-quality” humans (Geulen, 2007, p. 90).

The Twentieth Century: Genocide and Deconstruction

The most radical manifestation of this Social Darwinist framework appeared in National Socialism. Nazi racial hygiene was built on the notion of pure Aryan blood versus “bad” blood. Aryans were imagined as a master race whose living space needed to be expanded (Geulen, 2007, pp. 92–93). Central to the system was the construction of a supposedly “inferior” Jewish race. This provided the ideological justification for the Shoah. Moreover, racial classification was further diversified within Europe through additional categories such as Eastern, Alpine, Dinaric, and Mediterranean (Geulen, 2007, pp. 97–98).

After the second world war, UNESCO convened a committee of anthropologists and sociologists in 1949. They concluded that racial classifications had no scientific validity beyond trivial physiological variation (UNESCO, 1950). They affirmed that there were no meaningful differences in intelligence or character between so-called races.

Today, when people speak of “race,” they usually refer to national, cultural, or phenotypic differences. When we describe someone as a “Black person,” we are generally referring to skin color or an arbitrary phenotype rather than a biological race in any scientific sense. In contemporary science, human “race” is treated as a sociological concept (Kattmann, 2019, Smedley & Smedley, 2005, Lujan & DiCarlo, 2024).

Deconstructing the Myth with Biology

So, what is the exact answer of the biologists? If we can see clear differences in phenotype, maybe we do need to speak of “race,” even if it feels like the wrong word. Do we?

First of all, we need to be clear about what differences we are actually talking about. When we speak of genetic difference between any two individual humans, we are talking about a difference of only about 0.1% to 0.2% (Kim et al., 2023). There really isn’t much difference between humans in general. We are incredibly similar.

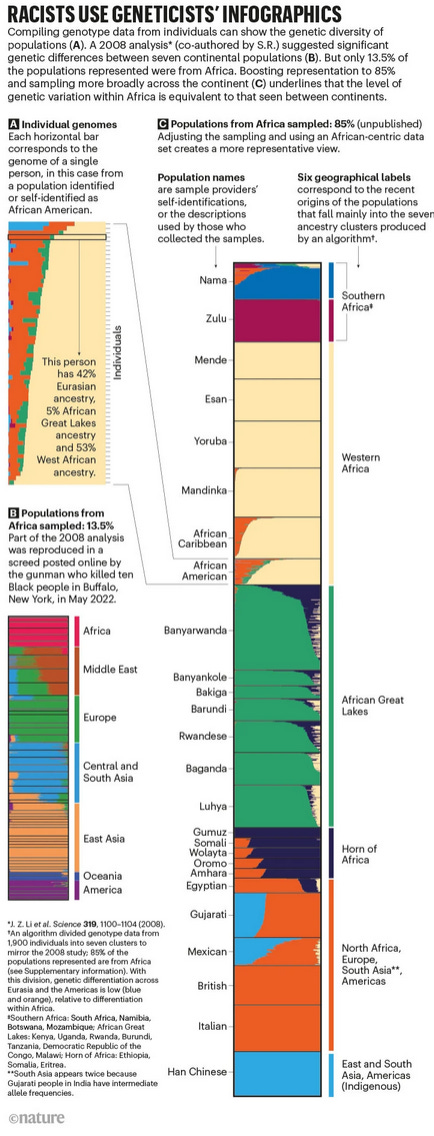

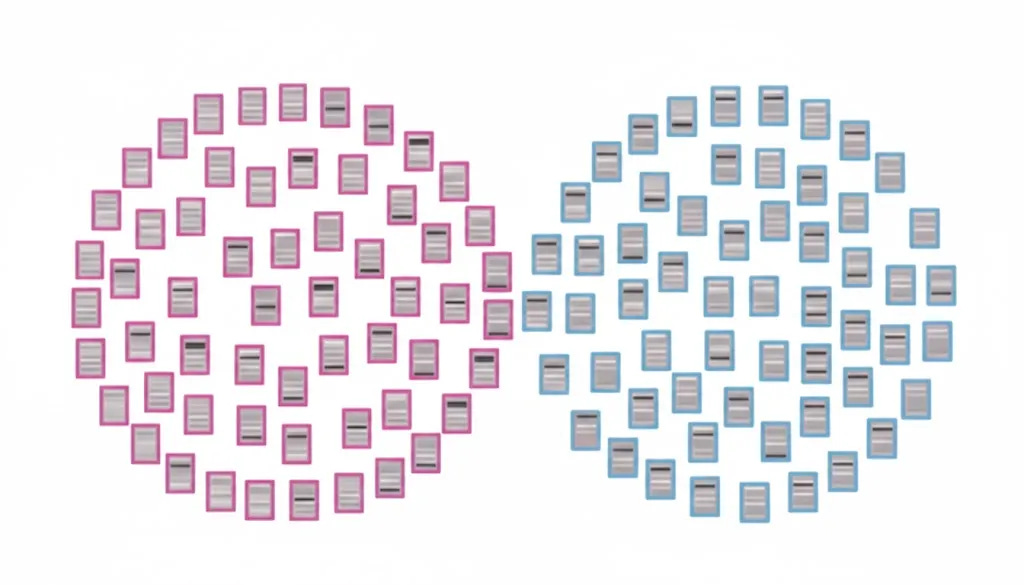

But now we want to speak of group differences. How genetically similar are different distinct “groups” of people defined by classical racial terms? Are they vastly different? Is there only a small overlap in their genetic makeup? If we visualize two distinct human groups as circles, biological reality looks like this: the circles representing these groups overlap almost entirely.

There are two key takeaways from this visual. First, look at the extremes, the “outer realms” of the circles. It is true that if we take someone from the extreme end of Group A and compare them to someone at the extreme end of Group B, we will see a significant difference.

Now look at the average difference within a single group. From one border of its circle to the other. The genetic variability within any one group we might call a “race” is huge. In fact, geneticists have found that if we look at the total genetic variation in the human species, about 85% to 90% of that variation exists within any given local population. Only about 10% to 15% of biological variation accounts for the differences between different continental groups. This means that the variation within any given race is greater than the variation between “races” (Rosenberg, 2011; Morey, 2023). This finding is confirmed by recent large-scale genomic research. Gouveia et al. (2025), for example, looked at 230,000 individual genomes and found a similar pattern.

To make this clear: if you go to a village in america, you will likely find a bigger genetic variability among the people in that one village than you would find between that village as a whole and a village in South Asia.

Of course, there have been critics of this analysis. Most notably, Edwards (2003) argued that while genetic variation might look small at a single locus, analyzing multiple loci simultaneously allows for highly accurate assignment of individuals to geographic groups. He termed the failure to see these correlations “Lewontin’s Fallacy” (as Lewontin was the first to find this pattern).

However, modern studies like Roseman (2021) have analyzed Edwards’ critique and found that he misidentified the aim of Lewontin’s argument. Lewontin was criticizing the utility of racial taxonomy, not the ability to assign individuals to groups using genetic data.

In this article, I am of course not denying that we can tell who comes from where, or that distinct phenotypic differences exist. Obviously, we can tell if there is a difference between someone from East Asia and Northern Europe. I can also distinguish a black dog from a brown dog of the same breed with 100% accuracy. But that doesn’t mean they belong to different races or subspecies just because their fur is colored differently.

This is the core of the misunderstanding: the ability to sort individuals based on geography (assignment) does not prove the existence of distinct evolutionary subspecies (taxonomy). As Roseman (2021) argues, Edwards conflates the correlation structures used for sorting with those required for evolutionary biological classification. For those interested in a deeper technical analysis of why Edwards’ claim fails, I recommend looking at Roseman (2021).

Understanding Genetic Gradients

Why is human variation continuous rather than categorical? The answer lies in our evolutionary history. About 100,000 years ago, Homo sapiens distributed from Africa over the whole world. First to the Middle East, then Europe, Asia, and beyond. But these groups almost always remained connected. There was constant genetic interbreeding at the margins (Templeton, 2023). It wasn’t as if one group went left, one group went right, and they never saw each other again, as happens with speciation in some animals.

This is why we cannot see clear distinct genetic groups, but a gradient of phenotypical difference. Imagine you take your bicycle and ride it halfway around the world. Let’s say we start in Germany, where I am right now, and ride east. When I cross the border into Poland, I wouldn’t see any abrupt difference. As I continue east, phenotypes might change slightly, maybe differences in average hair color or facial structure, but it’s subtle. As we go further south and east, it keeps changing bit by bit. Importantly, you will never cross a border and suddenly see a completely new skin color abruptly appear. It doesn’t happen. There is a continuous gradient of difference and not distinct categories (Serre & Pääbo, 2004, Lujan & DiCarlo, 2024).

Consensus vs. Cherry-Picking: What the Data Actually Says

I do not want to deny that some PCA studies using structure plots have produced what look like distinct genetic clusters that could, at first glance, be interpreted as “races.” Furthermore there are indeed a few studies that argue in favour of the classification in human races (see. Pigliucci, 2003). However, across the broader literature, this is not the scientific consensus. In my own review, only a small minority of studies suggested discrete racial groupings. Notably, and without this being a value judgment, those arguing in favor of racial categories were often philosophical in nature, whereas studies arguing against them were predominantly biological. The large majority of studies did not support discrete racial groupings.

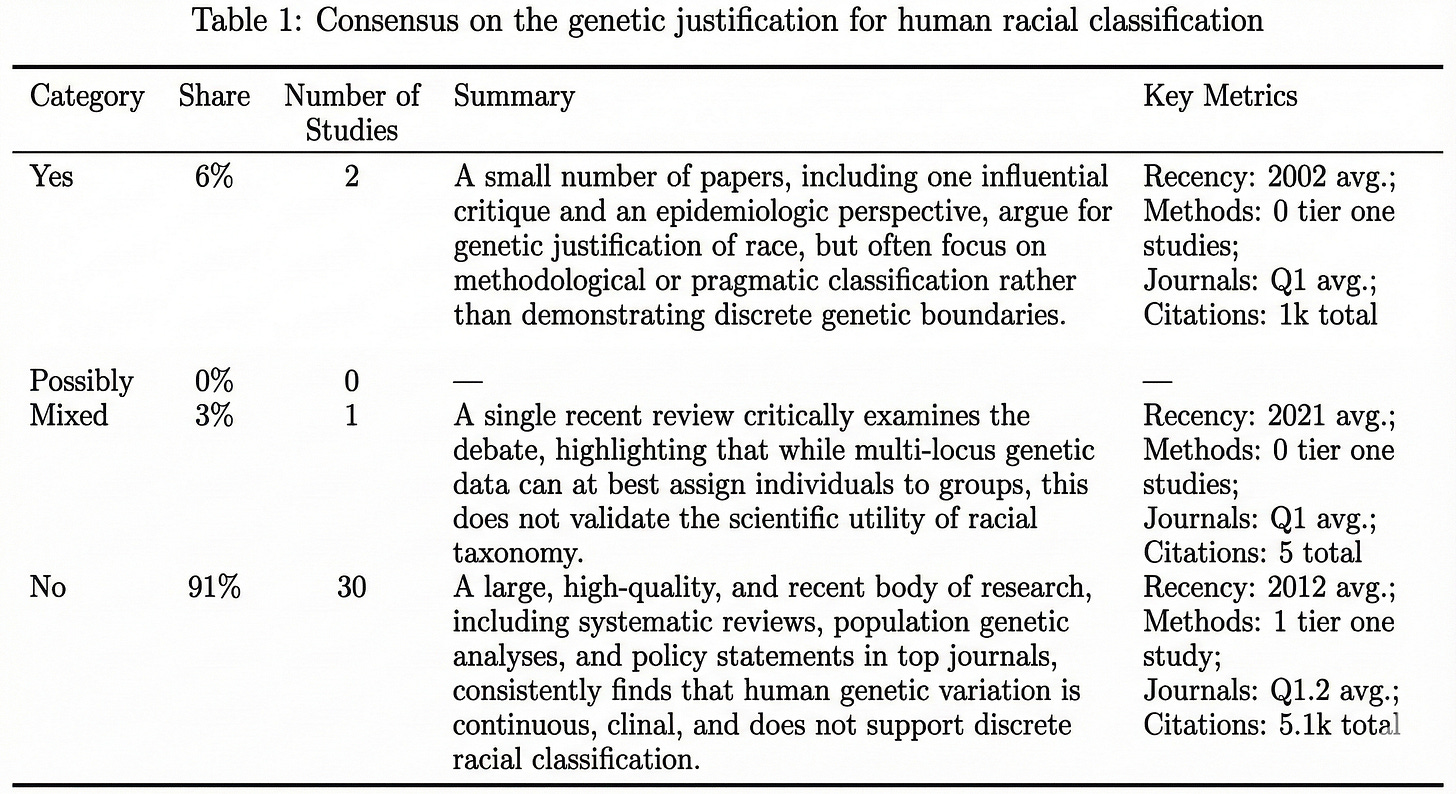

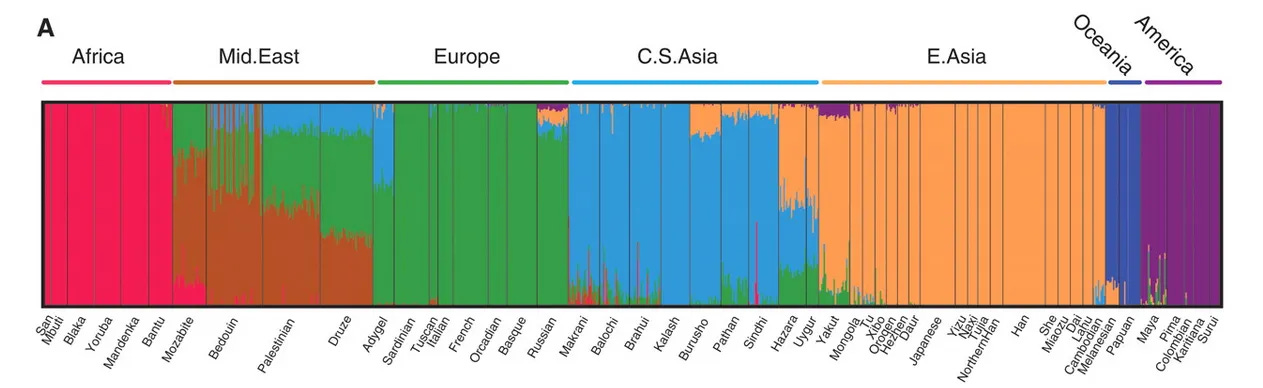

For example one study by Li et al. (2008) found this pattern.

To understand why these patterns appear, and why they are misleading, we first need to understand the statistical tools used to create them.

The Problem with Cluster Analysis and Structure Plots

The apparent clusters in some studies are largely artifacts of the analytical methods used, particularly “structure plot” analysis. The first major issue is that the structure plot we see is basically forced by our hypotheses on the data. In these analyses, the process begins by randomly assigning individuals to a predetermined number of groups (K). This means one has to preset the categories. As a result, even if the data does not inherently represent a categorical variable, it gets forced into that variable by the pattern we want it to look like in the end. Another issue which we often find in these studies are methodological problem in the sample selection.

A clear example of this issue is found in studies like Li et al. (2008). This article used a very small population of individuals native to Africa, which skewed the continuity of the data regarding the diversity of the African continent. By using limited samples from widely separated geographic regions (cherry-picking the cohort), they created artificial gaps.

Thus Carlson et al., (2022) write:

Our unpublished analysis shows that if the authors of the 2008 study had had access to more diverse dataset— with 85% of the populations selected from within Africa, and the other 15% from outside the continent — and had allowed for seven subdivisions of genetic ancestry as in the original study, the data from African populations would no longer fall into a neat cluster that lies apart from all the others (see ‘Racists use geneticists’ infographics’)

This sampling strategy made the data look categorically more distinct than it actually was (even though even in this data we can still see large overlaps between groups). When we feed this limited diversity into a structure plot that is already designed to find groups, we get category-like sections. But this structure is an artifact of the sampling, not the biological reality. For example, you could do the same thing with height and get arbitrary categories, even though height quite obviously is continuously distributed.

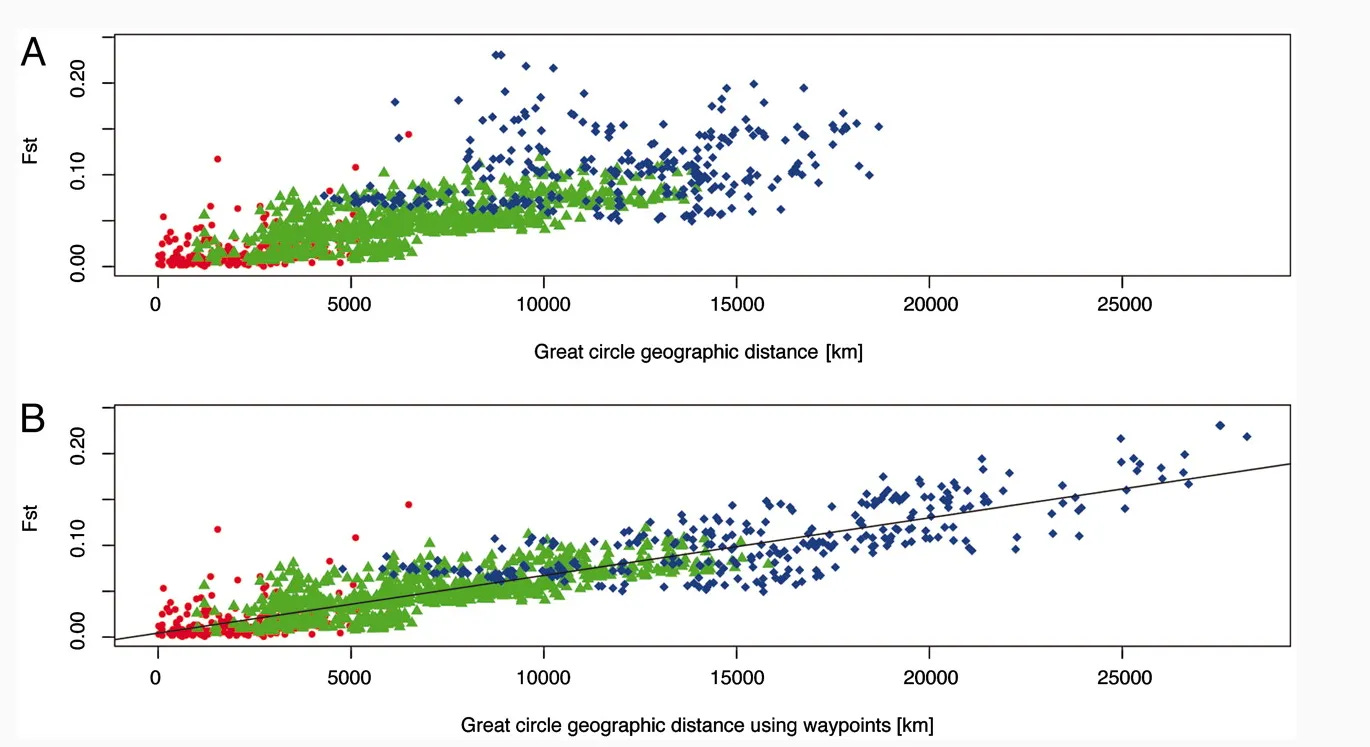

When we plot FST values without a structure that forces the data into preset categories, the data becomes continuous (Ramachandran et al., 2005). This aligns with what our evolution suggests: a history of migration and constant gene flow. When we collect data from bigger, more representative cohorts, the artificial boundaries dissolve.

Why Phenotype Misleads Us

Funnily enough, the phenotypes we usually talk about (like skin color) are very bad indicators of actual overall genetic similarity. For example, a study by Mallick et al. (2016) looked into the genetic differences between various groups. They examined genotypes from the Maasai in East Africa, the Khoisan in Southern Africa, and Greeks in Europe.

If one just looks at phenotypes, one might say: “Well, the Maasai and Khoisan are both “Black Africans”, so they are one race. The white Greek is a different “race.” But the genetic analysis showed that the Maasai and the Greeks are actually more genetically similar to each other than the Maasai are to the Khoisan. Thus, the shared skin color doesn’t reflect the underlying genetic reality.

Why? It makes sense if we look at the “Out of Africa” history. Humans originated in Africa, and they spent the longest time evolving there. Therefore, the deepest, oldest, and widest genetic diversity on Earth is found within the continent of Africa. The groups that migrated out of Africa were just a small subset of that original diversity, a genetic bottleneck. So, it is perfectly logical that two groups within Africa can be more genetically distant from each other than one African group is from a European group.

What This Means: The Biological Verdict

When we look at the whole picture, human diversity is clearly continuous. Some might be more similar, others might be less so, but there are no hard lines. This means human race is not a biological construct.

The central issue is that the boundaries used to define such differences can be drawn in countless ways, depending entirely on the criteria selected and the number of categories imposed in advance. One could, with equal plausibility, classify human populations according to hair color, nose morphology, or any number of other phenotypical traits. By the same logic, choosing skin color or geographic location as a basis for carving humanity into discrete groups lacks biological justification. When biologists identify subspecies, they rely on statistically significantly distinct, stable genetic clusters. Humans do not exhibit this pattern.

A clear illustration is the comparison with domestic dogs: dog breeds form tight genetic groupings because artificial selection in isolated groups has deliberately shaped them. Consequently, while dog breeds can be treated as distinct races in a biological framework, humans do not meet the same standard (Norton et al., 2019). Even chimpanzees can be subdivided into races but humans cannot (Templeton, 2013).

As Barbujani (2005) summarizes:

“The available studies show that there is geographic structure in human genome diversity, and that it is possible to infer with reasonable accuracy the continent of origin from an individuals multilocus genotype. However, clear-cut genetic boundaries between human groups, which would be necessary to recognise these groups as relatively isolated mating units which zoologists would call races, have not been identified so far. On the contrary, allele frequencies and synthetic descriptors of genetic variation appear distributed in gradients over much of the planet, which points to gene flow, rather than to isolation, as the main evolutionary force shaping human genome diversity. A better understanding of patterns of human diversity and of the underlying evolutionary processes is important for its own sake, but is also indispensable for the development of diagnostic and therapeutic tools designed for the individual genotype, rather than for illdefined race-specific genotypes.”

Debunking Myths of Intellect and Character

Now, beyond the claim that there are distinct biological races, it is often argued that these alleged races differ in intelligence, personality traits, or behavioral tendencies. Such claims are already problematic, given that biological races do not exist as discrete categories. Nevertheless, proponents may shift the argument and suggest that, within the continuous spectrum of human genetic variation, certain populations are supposedly less intelligent, more aggressive, or otherwise dispositionally different.

These arguments are frequently framed in geographic or national terms, for example by asserting that certain regions in Africa are genetically less intelligent. It is precisely at this point that abstract claims about biological race or population differences translate into concrete hierarchies of worth and ability. Examining these claims is therefore essential, because this is where the notion of race as a biological reality becomes a foundation for explicit racism.

Intelligence

The overwhelming weight of high-quality evidence indicates that observed acute differences between populations, are explained by environmental, social, and cultural factors rather than by genetic differences (Weiss & Saklofske, 2020; Tizard, 1974; Colman, 2016; Fagan & Holland, 2002, Pesta et al., 2020). Some researchers like Eysenck have argued for partial genetic explanations and have claimed that certain populations are less intelligent or more intelligent than others. However, these claims are not supported by modern molecular genetic evidence and face widespread criticism for substantial methodological and conceptual flaws (Colman, 2016). These include selection bias, inadequate or unrepresentative sample sizes, and the systematic overrepresentation of individuals drawn from disadvantaged conditions in certain regions. Consequently, such findings do not withstand contemporary scientific scrutiny.

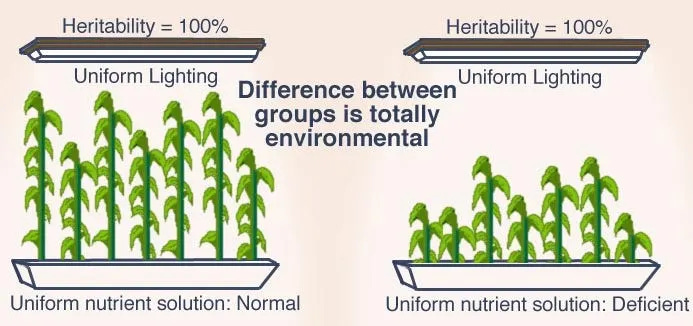

One crucial point is frequently misunderstood: the heritability of intelligence within a population does not imply that between-group differences are genetic. Heritability is context-dependent and does not account for environmental inequalities between groups.

As Lewontin (1970) famously argued, traits can show high heritability within groups while group differences are entirely environmentally driven. Consider the analogy of genetically identical plants grown in different pots. If both groups have a heritability of 100% for height, but one group receives adequate nutrients while the other receives a deficient nutrient solution, the latter will grow less tall despite identical genetic potential. This demonstrates that environmental conditions determine how genetic potential is expressed phenotypically. In the same way, environmental constraints shape cognitive development even when heritability estimates are high.

Further supporting environmental explanations, IQ gaps have narrowed over time, and in some cases disappear under conditions of equal opportunity, improved education, and reduced socioeconomic inequality (Dickens & Flynn, 2006).

Personality

The same question arises with respect to personality: are there differences in personality traits, including pathological dimensions such as psychopathy or aggression, between so-called races?

The current body of research does not support the existence of genetically based differences in personality, aggression, or psychopathy between socially defined racial groups (Zuckerman, 1990, 2003). Although early and controversial theories, most notably those associated with Lynn, posited such differences, these claims have been thoroughly criticized and rejected by more rigorous contemporary research (Zuckerman, 1990, 2003; Gorey & Cryns, 1995; Skeem et al., 2003).

Where small group differences in personality traits have been reported, they are best explained by environmental, cultural, and socioeconomic factors rather than genetic ones (Zuckerman, 1990, 2003; Földes et al., 2008; Dochtermann et al., 2019; Weidmann & Chopik, 2023; Murillo et al., 2024). While genetic factors do contribute to personality variation, with heritability estimates of roughly 40–50% within populations, this, again, does not imply that observed differences between socially defined racial groups are genetic in origin. As with intelligence, within-group heritability does not translate into between-group genetic causation.

Persistent claims about genetic differences in personality therefore rest on methodological weaknesses, selective reporting, and fundamental misunderstandings of gene–environment interaction (Zuckerman, 1990, 2003; Gorey & Cryns, 1995; Skeem et al., 2003). Accordingly, the use of race as a biological category in personality research is increasingly recognized as problematic, given the lack of genetic distinctiveness between racial groups and the overwhelming influence of social context.

Again, none of this implies that there are no differences in personality or intelligence between nations or populations. Such differences can and do exist, shaped by environmental conditions, educational systems, cultural norms, language, and socialization practices. These factors influence self-perception, behavior, and cognitive development, and they also place limits on cross-cultural measurement, particularly in personality questionnaires (Thalmayer et al., 2020). The central point, however, is that these differences are not inherently genetic. There is no population that is biologically predisposed to be more aggressive, more criminal, or more intelligent than another. Differences in outcomes may reflect unequal access to education or resources, but they do not reside in race, genes, or biology.

Thus we can conclude: despite persistent popular belief, differences in personality and intelligence (but also health) are often incorrectly attributed to fixed biological distinctions between racial groups, even though extensive scientific evidence shows that such groups lack clear genetic boundaries, consistent measurement, and biological validity (Lujan & DiCarlo, 2024).

The Language Games We Play

Now that we understand race is simply a sociological category superimposed by our linguistic use onto the biological continuous map of genetic differences between people, we should ask ourselves: should we use this term? Some might argue it makes our reality easier to navigate, it’s heuristic. While perhaps not the most detailed or accurate way to explain differences between people, it is what we have learned, part of our culture. So why shouldn’t we use it?

Wittgenstein and the Structure of Thought

To understand how deep this problem runs, we can look to the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. In his later works, he observed that language is not merely a set of labels we stick onto objects, but a dynamic system of “language games” that structure our very beliefs and reality. As he wrote:

“A language game is something that consists of repeated acts of playing in time.”

Our use of words forms a habit, and that habit forms a worldview. When we repeat a categorization often enough, it solidifies into a reality that we no longer question. Wittgenstein noted that the foundations of our understanding are not always objective facts, but rather a system of mutually supporting beliefs:

“The propositions describing this world-picture might be part of a kind of mythology.”

The Empirical Evidence: How Language Shapes Perception

This philosophical insight finds empirical support in contemporary cognitive science. As I argued in my article Does Language Shape Thought?, linguistic categories do not merely label preexisting distinctions; they can actively shape perception and cognition. Empirical work by Boroditsky demonstrates this clearly. Differences in temporal metaphors across languages are associated with different conceptions of time (Boroditsky, 2001), and linguistic variation in color terminology can lead to measurable differences in color perception itself (Boroditsky, 2018). These findings show that language can structure how the world is experienced, not merely how it is described.

Of course, temporal or color perception is not equivalent to the concept of race. However, the underlying mechanism is analogous. When we use the term “race,” the mind treats it as a real category, one that suggests distinct kinds of people rather than superficial variation within a single population. This effect is amplified by the fact that the same term is commonly used in zoological contexts, where categorical distinctions are sometimes biologically meaningful. As a result, the linguistic category itself makes it cognitively easier to associate groups with essentialized characteristics.

Language, then, may not strictly determine thought, but it functions as its vehicle. It provides the conceptual scaffolding through which reasoning, association, and interpretation occur. For this reason, we should not underestimate the foundational role of language in logic, philosophy, and psychology. Linguistic categories are central to how we make sense of the world.

Authoritarian regimes understand this connection intuitively, which is why they consistently attempt to police vocabulary and regulate permissible concepts. The recent efforts by the Trump administration to remove terms such as “diversity” from research funding provide a contemporary illustration. History provides a harrowing example of how this mechanism can be engineered. During the National Socialist regime, specific terms were weaponized to alter the moral landscape of a nation. Words like rassisch-hochwertig (racially high-value), arisch (Aryan), and Lebensraum (living space) were implemented into the daily use of language and, consequently, into the understanding of rights, virtues, and values.

This manipulation went so far that, in the end, even the euthanasia of disabled people, the killing of Jews classified as a “lower race,” and the existence of concentration camps were rationalized within this constructed linguistic reality. From the Nazis to modern authoritarian governments, the strategic manipulation of scientific language has served the same underlying purpose: to shape thought by shaping words. If those who seek to control thought grasp this mechanism so clearly, we should too.

The Subtle Power of Everyday Language

Of course, this is an extreme example. I do not mean to imply that using words like “race” or “subspecies” has such outcomes. However, it demonstrates the terrifying power of language to construct a “truth” that people act upon. In this sense, racism can be unintentionally reinforced through linguistic practices, even in the absence of explicit prejudice. This does not imply that the use of descriptors automatically entails racist intent.

I agree that phenotypical descriptions of populations are often necessary and practically unavoidable. However, given the demonstrable impact of linguistic framing on cognition and behavior, the choice of words matters. It is therefore imperative to select such words with conceptual caution rather than linguistic complacency.

A more modern example comes from Carlson et al. (2022), who found in their analysis that research papers portraying human populations as distinct biological clusters, through structure plots and FST values that can easily be misinterpreted as evidence for subspecies, correlate with increasingly violent behavior. While this should not be interpreted causally, in our polarized world where information is increasingly misused, we can see that such framing culminates in horrible events like the Buffalo shooting, which was partly justified through the uncritical misappropriation of scientific studies.

Biological Fiction, Social Reality

Some might argue: if everything is just a functional label anyway, why not simply use “race” as a convenient descriptor; indeed nothing has actually “clear lines”? Here’s why that doesn’t work: the word “race” implies statistically significant differences between humans, differences in intelligence, behavior, or personality, of the kind we see between distinct animal species. These differences simply do not exist in humans. We have better, more accurate ways to describe people: yes, we can say someone is Black, born in Germany, or speaks Mandarin, essentially, describing what we observe. It’s similar to distinguishing a black dog from a white dog within the same breed: these are useful phenotypical descriptions. Calling people “different races,” by contrast, adds nothing but confusion. Most countries function perfectly well without misusing the word “race.” Using it imports false implications of fundamental biological differences that aren’t there. Functionally, it is the wrong label for the reality we are trying to describe.

However, “Black people” or “White people” clearly exist as social categories. Through language, these groups become real in their consequences: they can for example be discriminated against as unified groups, they shape identity, they structure societies. This language game creates a social reality independent of biological fact. We cannot change this linguistic legacy overnight, but we must recognize it for what it is: a social construction with very real effects, not a reflection of genetic boundaries.

Funnily enough, there is a historical coincidence that underscores this: both Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher who deconstructed language, and Adolf Hitler, the dictator who weaponized it, attended the same school, the Kaiserlich-Königliche Realschule in Linz. That might tell you something about the divergent potentials of language.

Ultimately, we are left with Wittgenstein’s observation on how reality is effectively voted upon by the words we agree to use:

“So you say that the agreement of people decides what is right and what is wrong? — Right and wrong is what people say; and in the language the people agree. This is not an agreement of opinions, but of the form of life.”

Solutions in sight?

We should either increasingly emphasize that race is a shifting social, historical, and political construct, as Carlson et al. (2020) write, or we should use another language entirely. Race is primarily a biological term in zoology, so its application to humans, where such categories do not exist, is inherently misleading and reinforces pseudoscientific framing.

But let me be clear, simply replacing one word with another will not solve the problem. What I am advocating against is the widespread practice of categorizing people into distinct biological clusters, a framework that many people still understand as reflecting biological reality. We need to reshape our “language game” around human diversity, moving toward an understanding of biological reality as a continuous spectrum without categorical differences in character or intelligence between populations.

Importantly I think this transformation requires education, not authoritarian regulation. We cannot legislate language change, but we can promote it through increased awareness: explaining what FST values actually measure, how clustering studies produce their results, what the scientific consensus says about supposed character or intelligence differences, and how our current racial categories emerged historically. Many people, perhaps more than we realize, still believe that biological races exist in any meaningful sense.

Beyond education, we must reform how genetic research is visualized and communicated. Carlson et al. (2020) recommend ensuring all populations are represented equally in genetic variant research and selecting data more carefully for analysis. They note that figures using principal component analysis or structure plots are compelling for press releases but easily misunderstood by lay audiences. Journals should therefore require, as Carlson et al. (2022) suggest, that axes of cluster plots be clearly explained or labeled to indicate what proportion of total human genetic variation is actually represented. In an age of social media, geneticists must anticipate that visualizations could be stripped of context and misinterpreted.

Ultimately, the solution is multifaceted: better terminology, transformed conceptual frameworks, widespread education, and clearer scientific communication standards.

Conclusion

As I have explained, the variation within human populations is so complex that classifying humans into discrete races is biologically meaningless (Gould, 1984). Genetic variation within a single population often exceeds that between populations—two individuals from different African regions can be more genetically distinct from each other than either is from a European or Asian individual. Human populations have always interbred, creating continuous genetic gradients rather than isolated groups (Cavalli-Sforza, 1992). We’re a young species; no population has been isolated long enough to develop the fixed differences that would justify racial classification.

Rejecting “human races” is not claiming human exceptionalism, rather it is quite clearly grounded in biology and evolutionary theory. The out-of-Africa hypothesis reminds us that all humans share recent African ancestry. Just as European immigrants didn’t constitute a new race in America, our ancestors didn’t form biologically distinct races.

While I don’t claim to have a definitive replacement term or that changing one word will end racism, we should be aware of the problems this potentially gives rise to. Geneticists must clarify their visualizations and communicate findings precisely. We should consider discontinuing the term “race” or explicitly frame it as a socially imposed grouping rather than a biological category. Moreover we should transform the conversation around human diversity through education, replacing the myth of discrete biological races with an understanding of continuous human variation.

So, if you know someone who still believes biological human races exist, share this article. That's my goal today: to change the worldview of at least some readers. This article provides you with the argumentative and evidentiary foundation to counter any claim that human races are biologically real.

As Kattmann (2019) concludes:

“Anyone who continues to speak scientifically of human races must explain in what sense this could be appropriate and justified, especially in light of the historical consequences of the concept. This demand is not a prohibition of thought, but an imperative to question habitual ways of thinking and to reflect on the ethical implications of the concepts we use. Scientists are responsible not only for the actions they take but also for the thinking they suggest or encourage.”

Further aids

I used LLM (large-language-models) for this article as outlined in my article for responsible AI use, which you can read here:

References

Barbujani, G. (2005). Human races: Classifying people vs understanding diversity. Current Genomics, 6(4), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389202054395973

Berg, R., & Bailey, D. (2024). Race and ethnicity in physiological research: When socio‐political constructs and biology collide. Experimental Physiology, 109(9), 1238–1239. https://doi.org/10.1113/ep091409

Boroditsky, L. (2001). Does language shape thought? Mandarin and English speakers’ conceptions of time. Cognitive Psychology, 43(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.2001.0748

Boroditsky, L. (2011). How languages construct time. In S. Dehaene & E. Brannon (Eds.), Space, time and number in the brain (pp. 333–341). Academic Press.

Boroditsky, L. (2018). How language shapes the way we think. TED.

Brooks‐Gunn, J., Klebanov, P. K., & Duncan, G. J. (1996). Ethnic differences in children’s intelligence test scores: Role of economic deprivation, home environment, and maternal characteristics. Child Development, 67(2), 396–408.

Carlson, J., Henn, B. M., Al-Hindi, D. R., & Ramachandran, S. (2022). Counter the weaponization of genetics research by extremists. Nature, 610(7932), 444–447. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03252-z

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. (1992). Stammbäume von Völkern und Sprachen. Spektrum der Wissenschaft, 1, 90–98.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P., & Piazza, A. (1996). The history and geography of human genes. Princeton University Press.

Colman, A. (2016). Race differences in IQ: Hans Eysenck’s contribution to the debate in the light of subsequent research. Personality and Individual Differences, 103, 182-189

de Gobineau, A. (1852). Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines. Didot.

Dickens, W., & Flynn, J. (2006). Black Americans Reduce the Racial IQ Gap. Psychological Science, 17, 913 - 920. 9280.2006.01802.x

Duello, T., Rivedal, S., Wickland, C., & Weller, A. (2021). Race and genetics versus ‘race’ in genetics: A systematic review of the use of African ancestry in genetic studies. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 9(1), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eoab018

Edwards, A. W. F. (2003). Human genetic diversity: Lewontin’s fallacy. BioEssays, 25(8), 798–801.

Fagan, J., & Holland, C. (2002). Equal opportunity and racial differences in IQ. Intelligence, 30, 361-387. 2896(02)00080-6

Frey, C. (1992). Verantwortung nicht nur für das Handeln, sondern auch für das Denken. In H. Preuschoft & U. Kattmann (Eds.), Anthropologie im Spannungsfeld zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik (pp. 1–18). Oldenburg.

Fuentes, A., Ackermann, R., Athreya, S., Bolnick, D., Lasisi, T., Lee, S., McLean, S., & Nelson, R. (2019). AAPA statement on race and racism. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 169(3), 400–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23882

Geiss, I. (1988). Geschichte des Rassismus. Suhrkamp.

Geulen, C. (2007). Geschichte des Rassismus. C.H. Beck.

Gorey, K., & Cryns, A. (1995). Lack of racial differences in behavior: A quantitative replication of Rushton’s (1988) review and an independent meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(3), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(95)00050-g

Gould, S. J. (1984). Warum wir menschliche Rassen nicht benennen sollten – eine biologische Betrachtung. In S. J. Gould, Darwin nach Darwin (pp. 195–200). Ullstein.

Gouveia, M. H., Meeks, K. A., Borda, V., Leal, T. P., Kehdy, F. S., Mogire, R., ... & Rotimi, C. N. (2025). Subcontinental genetic variation in the All of Us Research Program: Implications for biomedical research. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 112(6), 1286–1301.

Jahn, I., Löther, R., & Senglaub, K. (Eds.). (1985). Geschichte der Biologie. Gustav Fischer Verlag.

Jorde, L., & Wooding, S. (2004). Genetic variation, classification and ‘race’. Nature Genetics, 36(Suppl 1), S28–S33. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1435

Kattmann, U. (2019, August 3). Rassismus, Biologie und Rassenlehre. Zukunft braucht Erinnerung. https://www.zukunft-braucht-erinnerung.de/rassismus-biologie-und-rassenlehre/

Kim, B. J., Choi, J., & Kim, S. H. (2023). On whole-genome demography of world’s ethnic groups and individual genomic identity. Scientific Reports, 13, Article 6316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32325-w

Kleingeld, P. (2007). Kant’s second thoughts on race. The Philosophical Quarterly, 57(229), 573–592.

Kleingeld, P. (2011). Kant’s third thoughts on race. In R. Bernasconi (Ed.), Reading Kant’s Geography (pp. 291–318). SUNY Press.

Krüger, A. (1998). A horse breeder’s perspective: Scientific racism in Germany 1870–1933. In N. Finzsch & D. Schirmer (Eds.), Identity and intolerance: Nationalism, racism, and xenophobia in Germany and the United States (pp. 371–396). Cambridge University Press.

Lala, K., & Feldman, M. (2024). Genes, culture, and scientific racism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(1), Article e2322874121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2322874121

Lewontin, R. C. (1972). The apportionment of human diversity. In T. Dobzhansky, M. K. Hecht, & W. C. Steere (Eds.), Evolutionary Biology (Vol. 6, pp. 381–398). Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Li, J. Z., Absher, D. M., Tang, H., Southwick, A. M., Casto, A. M., Ramachandran, S., ... & Myers, R. M. (2008). Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science, 319(5866), 1100–1104.

Long, E. (1774). The history of Jamaica (Vol. 2). T. Lowndes.

Long, J., Li, J., & Healy, M. (2009). Human DNA sequences: More variation and less race. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21011

Lujan, H. L., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2024). Misunderstanding of race as biology has deep negative biological and social consequences. Experimental Physiology, 109(8), 1240–1243. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP091491

Morey, R. (2023). What is the biological basis for race - Implications for psychiatric genetics. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 75, S47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2023.08.095

Mosse, G. L. (2006). Die Geschichte des Rassismus in Europa. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag.

Norton, H. L., Quillen, E. E., Bigham, A. W., Lindo, J., & Parra, E. J. (2019). Human races are not like dog breeds: Refuting a racist analogy. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 12, Article 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-019-0109-y

Pigliucci, M., & Kaplan, J. (2003). On the concept of biological race and its applicability to humans. Philosophy of Science, 70(5), 1161–1172. https://doi.org/10.1086/377397

Ramachandran, S., Deshpande, O., Roseman, C. C., Rosenberg, N. A., Feldman, M. W., & Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. (2005). Support from the relationship of genetic and geographic distance in human populations for a serial founder effect originating in Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(44), 15942–15947. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507611102

Roseman, C. C. (2021). Lewontin did not commit Lewontin’s fallacy, his critics do: Why racial taxonomy is not useful for the scientific study of human variation. Bioessays, 43(12), 2100204.

Rosenberg, N. A. (2011). A population-genetic perspective on the similarities and differences among worldwide human populations. Human Biology, 83(6), 659–684. https://doi.org/10.3378/027.083.0601

Royal, C., & Dunston, G. (2004). Changing the paradigm from ‘race’ to human genome variation. Nature Genetics, 36(Suppl 1), S5–S7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1454

Serre, D., & Pääbo, S. (2004). Evidence for gradients of human genetic diversity within and among continents. Genome Research, 14(9), 1679–1685. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.2529604

Smedley, A., & Smedley, B. D. (2005). Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American Psychologist, 60(1), 16–26.

Templeton, A. R. (1998). Human races: A genetic and evolutionary perspective. American Anthropologist, 100(3), 632–650. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.632

Templeton, A. R. (2013). Biological races in humans. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 44(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.04.010

Templeton, A. R. (2023). The importance of gene flow in human evolution. Human Population Genetics and Genomics, 3(3), Article 0005. https://doi.org/10.47248/hpgg2303030005

Thalmayer, A. G., Saucier, G., Ole-Kotikash, L., & Payne, D. (2020). Personality structure in East and West Africa: Lexical studies of personality in Maa and Supyire-Senufo. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 1132–1152. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000264

Tizard, B. (1974). IQ and Race. Nature, 247, 316-316. https://doi.org/10.1038/247316a0

UNESCO. (1950). The race question. UNESCO.

von Linné, C. (1758). Systema Naturae (10th ed.). Salv.

Weiss, L., & Saklofske, D. (2020). Mediators of IQ test score differences across racial and ethnic groups: The case for environmental and social justice. Personality and Individual Differences, 161, 109962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109962

Wittgenstein, L. (1969). Über Gewissheit (On Certainty). (Nr. 95). (G.E.M. Anscombe & G.H. von Wright, Eds.). Harper & Row.

Wittgenstein, L. (1989). Philosophische Untersuchungen (Philosophical Investigations). In Werkausgabe in 8 Bänden, Band 1: Tractatus logico-philosophicus, Tagebücher 1914-1916, Philosophische Untersuchungen (Nr. 241/329). Suhrkamp Verlag.

Yudell, M., Roberts, D., DeSalle, R., & Tishkoff, S. (2016). Taking race out of human genetics. Science, 351(6273), 564–565. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4951

Zuckerman, M. (1990). Some dubious premises in research and theory on racial differences: Scientific, social, and ethical issues. The American Psychologist, 45(12), 1297–1303. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.45.12.1297

Zuckerman, M. (2003). Are there racial and ethnic differences in psychopathic personality? A critique of Lynn’s (2002) racial and ethnic differences in psychopathic personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(6), 1463–1469.

Ludwig and Hitler were both in the same school, haha!! I never knew that. For about 2–3 months I had an idea for an article about how skin color developed in different peoples on different continents, more about melanin production and environmental factors like sunlight and how it saves from UV rays. But I thought people might take it as a racist standpoint, so I ended up dropping the idea.

This is detailed. Thank you. It's strange to me that people see diverse phenotypes as anything other than being influenced by genetic drift and other natural pressures, none of which have led to any recent speciation of homo sapiens sapiens; i.e., we are "inbred" on a global scale.

*I apologize for the typos.